We are delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the Brearley essay prize is Henry Rugg’s essay on ‘What makes a country powerful?’. This year the standard of entries was particularly high so we’d like to congratulate all those who submitted essays. The winning essay can be read below.

What makes a country powerful? Henry Rugg, Dame Alice Owen’ School

A Tale of Two Cities

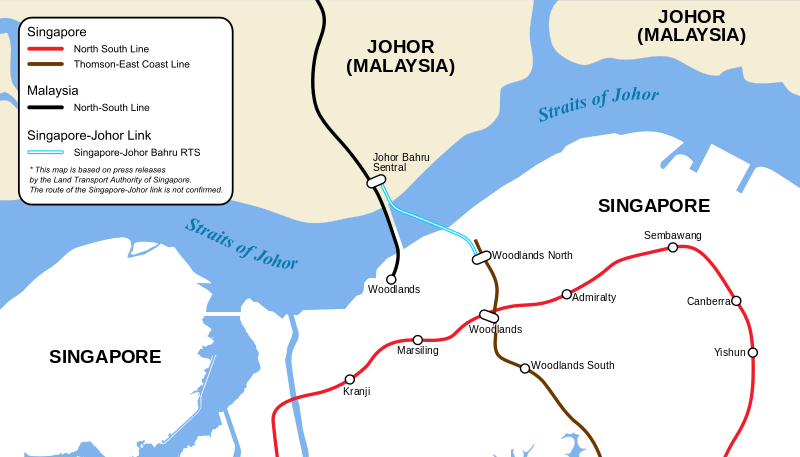

The Malaysian city of Johor Bahru is connected to Singapore by a causeway merely a kilometre in length. Both cities are located at the southern tip of the Malay peninsula, share the same equatorial climate and temperature, and share the geographical advantage of being at the nexus of major shipping lanes that connect the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. Location-wise, Johor Bahru and Singapore couldn’t be more similar. But the economic differentials tell a markedly different story; Singapore’s GDP per capita is over 8 times greater than Johor’s (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2021). The differences in the standard of living are equally stark: a person living in Singapore can expect to live around ten years longer than their neighbour in Johor (data.worldbank.org, 2022), which to put it in perspective, is the same difference in average life expectancy between the UK and Iraq. Furthermore, a Singaporean can expect access to government-subsidised housing and universal healthcare of a quality that the Malaysian government simply doesn’t have the money or resources to compete with. But given that Malaysia is considerably larger than Singapore (470x times larger to be precise) and has six times the number of people, you would surely expect Malaysia to have a better funded, better equipped military. Such an assumption would be incorrect; in 2022 Singapore’s defence budget of $15.8 billion staggeringly exceeded Malaysia’s budget of $3.9 billion (globalfirepower, 2023).

How can two countries be so close yet so different? Why is Singapore considerably smaller than Malaysia yet considerably more powerful? The vast disparities between Singapore and Malaysia can be explained by the divergent paths these nations took after the British relinquished colonial rule in the 1950s; Singapore created economic and political systems that generated growth and prosperity for the vast majority of its citizens, whilst Malaysia did not. In parsing the systemic differences between Singapore and Malaysia, this essay will establish a framework for power, viewed through the lens of a country that has not been endowed with a wealth of natural resources or land, but whose rise to power over the last half-century has hinged upon the strength of its economic and political systems.

Pluralistic political and economic systems

Power and prosperity are intimately linked- without creating sufficient wealth a country cannot fund its defence, provide public services and technologically innovate. For a country to generate prosperity, and with it power, it must establish ‘pluralistic’ economic and political systems.

A pluralistic economic system fosters economic activity, productivity, and prosperity for the benefit of broad subsets or ‘pluralities’ of people in society, not just for the benefit of a ruling political elite. The conditions that underlie a pluralistic economic system are an unbiased system of law, the provision of public services to create a level playing ground, and well-enforced property rights that are enshrined within the law- since an entrepreneur or business person who expects their produce to be expropriated or taxed away by the state has little incentive to produce. It is imperative that an economic system is based on pluralism, creating a society whereby anyone with a good idea can start a business, any person with a gift or talent for a particular activity can pursue it, and better, more efficient firms can routinely replace less efficient ones. The opposite of this is a repressive economic system designed by a ruling elite to enrich one subset of the population at the expense of the working population ie. kleptocracy.

Where political power is repressive and unrestrained, it is in the interest of such absolutist leaders to create a political system that props up their power and allows them to extract resources and wealth from the economy to enrich themselves. Where the political system is pluralistic however, political power is distributed across a broad coalition of groups instead of being vested in a single individual or group; politicians are beholden to the will of the population and must yield to popular vote.

State involvement; a balancing act

Invariably, the state is inextricably connected to the creation of a pluralistic economic system because it falls upon the state to provide public services, enforce the law and uphold private property and proprietorship. Put another way, the success of an economic system is wholly dependent on politics, in what German philosopher Max Weber describes as the state’s ‘monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force’ (Weber, 1921). But too much force, or too much centralisation may strip away the incentives to produce altogether.

Although Singapore is held in high regard by many economists for being the standard bearer of market friendliness and market openness (Heritage Foundation, 2022), and for good reason, Singapore’s economic success is also down to several successful interventions by its government. Formed in 1960, the Singapore Housing and Development Board (HDB) was formed to provide affordable and high-quality housing for its residents, issuing properties on 99-year leaseholds. The programme has been an enormous success- more than 80% of Singapore’s 5.4 million residents live in housing subsidised by the government (Bryson, 2019). The fact that the government owns most of the housing in Singapore carries several additional benefits; it allows the government to enforce a restriction on citizens owning more than two residential homes, keeping supply high and prices affordable, whilst also allowing it to enforce minimum levels of occupancy of each of the main ethnic groups in the city — Chinese, Malay and Indian — to prevent the formation of “racial enclaves” and promoting racial integration (Bloomberg, 2020). A similar system of state sponsorship exists in Singapore’s Medifund system; powered by a three billion dollar endowment, the government uses the fund’s investment income to pay medical bills for those in financial need. Remarkably, more than 99% of applicants to Medifund are approved (International Citizens Insurance, 2021).

Of course, the Singaporean system is not a replicable template for every economy due to Singapore’s unique position as a small island city-state, but that misses the point. The central argument of this section is certainly not that the state should preside over markets, or even that every country ought to follow the same policies that worked well for Singapore, but rather through the creation of a pluralistic political system, the state can enhance the functioning of an economy in ways that the market simply can’t.

Wealth equals diplomatic power

Whilst being less than half the size of the country of Hertfordshire, Singapore had forged strong diplomatic alliances with the likes of China and the US, in spite of its lack of land mass, population and natural resources. This is chiefly because these superpowers have a vested interest in keeping Singapore their ally; Singapore is a leading exporter of financial services, computer chips (OEC, 2022) and houses an immense intellectual capital, not least due to its world-class education system. Over the last two decades, Singapore has consistently ranked near or at the top of the World Bank’s ‘ease of doing business’ report (Worldbank, 2019), has been listed by the Economist Intelligence Unit as the number one country for its ‘efficient and open economy,’(BBC, 2014) and is one of the few nations to receive a AAA credit rating (tradingeconomics.com, 2023), deeming the possibility of a default on its debt massively unlikely. The reason that foreign nations such as China and the US like doing business with Singapore, and hence have strong, mutually beneficial diplomatic ties with Singapore, is because of its well-enforced rule of law, lack of political corruption and strong property rights.

Malaysia, despite a larger population and abundance of natural resources, is not a formidable global superpower, and its problem is systemic. In a compelling report by Transparency International in 2012, Malaysian companies were found most likely to accept a bribe. In the same report, 50% of foreign businesses felt that they had lost out on business in Malaysia due to their competitors’ bribes being accepted by Malaysian officials (Wall Street Journal, 2012). Nothing illustrates Malaysia’s long-standing struggle with corruption more strikingly than the ‘1 Malaysia Development Berhad’ Scandal in 2015, in which Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund was systematically embezzled by its president and his cronies to the tune of $4.5 billion, in one of the largest financial scandals in history (BBC, 2019). In a political and economic environment where corruption runs rife, foreign countries are simply less likely to do business with Malaysia, and subsequently less likely to create enduring, mutually beneficial diplomatic connections.

Wealth equals military power

In 1966, Singapore’s first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew made a bold statement of intent: Singapore must become a ‘poisonous shrimp’ to survive in a world of ‘big fish.’ Singapore has become just that. The country’s vast wealth enables it access to the best military equipment available; due to its flourishing private markets, much of Singapore’s military equipment is either produced or improved upon by its own defence companies (Business Insider, 2018). Due to its strong international relations, Singapore’s small size is not a limiting factor when it comes to its military; Singapore has struck deals with the US, Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan to allow them to place personnel and air squadrons overseas.

Malaysia, despite its superior manpower, is a lesser military force. Hobbled by huge public debt, a slipping currency and flagging economic growth, Malaysia has recently agreed on a barter in which it exchanges its palm oil for European military equipment- an alarming indication of the available funds for its military (FMT, 2021). Malaysia operates a considerably smaller fleet of aircraft than Singapore (globalfirepower, 2023), and much of the aircraft it has is not operational due to a lack of funds for maintenance (mymilitarytimes.com, 2021). The military disparity between Singapore and Malaysia exists because of their vastly different economies – Malaysia simply doesn’t produce enough wealth to maintain its military operations, nor does it innovate and update its military equipment in the way that Singapore is able to.

The virtuous cycle

Pluralistic economic and political systems create a cycle of positive feedback. The political system is upheld by positive incentives; politicians cannot extract resources from the economy because they are bound by the ballot of the public who can simply decide to not reelect them. As the political system begins to represent a broad plurality of groups, the great mass of people inevitably vote for policies that will enrich the broader population and not just a narrow elite. As the law is upheld and property rights are secured, any person with vision can set up a business and monetise their ideas, encouraging innovation, and in aggregate creating a more prosperous, advanced society. Much as it did in Singapore, increased wealth leads to increased government funding of the defence sector, and gives a country security should conflict arise, whilst improvements in technology lead to the creation of more effective military deterrents. This path to power is by no means a rigid archetype – Britain’s path has been different to Singapore’s due to their geographical differences for example – but their established position as global powers is hinged upon their successful pluralistic political and economic systems.

When a country embarks on the virtuous cycle of pluralism, growth and innovation it is not always a straight and narrow path; it took Britain over a century to develop and refine modern democracy from the initial extension of the franchise in 1832, and for the US it entailed a civil war. But it is in the crucible of this virtuous cycle – with all its difficulties – that lasting, enduring power is forged.